Background

Since 2005, Jut and collaborators have conducted numerous cave projects on the southern Colorado Plateau in the southwestern United States. These studies have characterized cave-dwelling arthropod communities, identified and monitored bat roosts, quantified habitat of selected species, and examined the efficacy of arthropod sampling techniques. Additionally, they discovered at least 30 species new to science — 10 of which have been formally described in scientific papers.

This work occurred primarily on Grand Canyon-Parashant, Wupatki, and El Malpais national monuments. This page provides an overview of the findings from each of the three National Park Service monuments.

Prior to their work, most of the research conducted in the southern Colorado Plateau was baseline in nature. It is hoped that the combination of previous work with these more contemporary studies will help develop a regional picture of cave-dwelling animals, their distributions, and their habitats.

Parashant

Grand Canyon-Parashant National Monument (Parashant) is located in northwestern Arizona, United States. Spanning approximately 1,638 square miles (2,636 km2), the monument is characterized by rugged terrain containing deeply incised canyons, mesas, and mountains. Vegetation zones include plants characteristic of the Mojave Desert at lower elevations, grading through grassland and juniper shrubland to ponderosa pine forest on Mt. Trumbull (elevation 8,028 ft; 2,447 m).

In the summer of 2005, Jut and Kyle Voyles launched the first study to examine the cave-dwelling arthropods, bats, and other vertebrates on the Parashant. This work burgeoned into several other projects, which spanned nearly a decade. Their objectives were to: (1) catalog all macro-taxa using caves, including the identification of endemic and sensitive subterranean-adapted invertebrates; (2) apply and evaluate an experimental systematic sampling framework for inventorying arthropods; (3) draw between-cave comparisons to gain inference into patterns of invertebrate species’ distributions, endemism, biodiversity, and biogeography; (4) monitor cave-roosting bat populations; (5) characterize habitat of caves with sensitive biological communities; and, (6) provide recommendations to protect the sensitive cave biological resources.

Results

Through their efforts, 53 arthropod morphological species groups (morphospecies) including 10 troglobionts and one obligate troglophile were identified. They also discovered four possible bat maternity roosts and two hibernacula. These roosts supported at least three species including Townsend’s big-eared bat (Corynorhinus townsendii), pallid bat (Antrozous pallidus), and fringed myotis (Myotis thysanodes).

Other vertebrates using Parashant caves included the woodrat (Neotoma spp.), American porcupine (Erethizon dorsatum), barn owl (Tyto alba), Panamint rattlesnake (Crotalus stephensi), and western diamondback rattlesnake (Crotalus atrox). They also encountered small carnivore scat in many of the caves surveyed, which may be ringtail cat (Bassariscus astutus) – as this species is known to hunt bats in caves and has been routinely observed in caves in the neighboring Grand Canyon National Park.

Future Research and Management

Fortunately, Parashant is a rather isolated national monument. By virtue of its remoteness, caves occurring within the monument’s boundary are afforded a certain level of protection. However, as the human population of St. George, Utah continues to grow, people will inevitably exert more pressure on the monument’s natural resources. Land managers should continue to monitor cave visitation and be prepared to revisit how best to protect sensitive resources as recreationalists amplify their outdoor activities outside of the city.

Additional arthropod research: A troglomorphic anopsobiid centipede was identified in two caves (including the cave mentioned above). It has been presently identified as Buethobius cf. arizonicus. However, it likely represents at least one species new to science. Additional specimens should be collected so the animal may be properly examined and potentially described. Moreover, papers describing new species of cave-dwelling springtails and terrestrial isopods need to be prepared — as many species are likely to be single cave or regional endemics and thus important to conservation, management, and planning.

Courtesy Kyle Voyles.

Additional bat studies: The three caves supporting summer roosting bats should be closed to recreational use until the function of these sites can be determined. In other words, are these caves maternity roosts? If they are maternity roosts (and they probably are), seasonal closures should be considered.

Closure of caves with high arthropod diversity and single-cave endemics: Three caves represent the most diverse arthropod communities and contain subterranean-adapted taxa. Most of these troglomorphic species are single-cave endemics. Given the hyper-restricted distributional range of these species, deep zone environments of these caves should be closed to recreational use.

To gate or not to gate: Gating a cave should only be done as a last resort. Land managers had considered gating one of the caves, which has an extraordinary diversity of arthropods. This cave supports an undescribed and new genus of troglophilic cricket, at least four troglobionts (all believed to be single cave endemics), and at least two beetle species new to science. Given that the entrance is south-facing, a steel gate heated by the summer sun may artificially increase the cave’s temperature and potentially reduce humidity. As troglobionts (and troglophiles) are generally limited to narrowly defined climatic requirements, these likely environmental changes may render the cave habitat unsuitable. Thus, such a management decision may result in the extinction of one or more of these species. Gating is not recommended.

since the ancients. Left to right, Ty Spatta, Kyle Voyles, and Jut. Parashant National Monument. Courtesy Kyle Voyles.

Wupatki

Wupatki National Monument (Wupatki) is located in north-central Arizona, approximately 25 miles (40 km) north by northwest of the city of Flagstaff. With an area of 91 square miles (143 km2), elevation range from 4,297 ft (1,310 m) along the Little Colorado River to 5,594 ft (1,705 m) near the southwestern corner of the monument. Vegetation includes juniper savanna (Juniperus spp.), Colorado Plateau arid grassland, and a variety of Colorado Plateau shrubland associations. The monument is comprised of mesas, plains, canyons, bluffs, and badlands with topography further sculpted by tectonic driven seismic activity. Localized uplift was probably caused by volcanism in the surrounding the San Francisco Volcanic Field over the past 65 million years. More recently, some geologic features continued to rise and deform, creating an extensive network of visible fractures. These features expanded to form subterranean “earth crack” fissures or caves. Six of these earth cracks are large enough for humans to enter.

Previous cave biological studies at Wupatki have been limited. Prior to the Jut’s work, 19 cave-dwelling arthropod species were identified; however, none of these animals were troglobionts. Of note, one presumed endemic troglophilic pseudoscorpion (Archeolarca welbourni) was found in two earth cracks and later formally described. For bats, the most extensive study was conducted in during the winter of 1986. Researchers identified all six earth cracks as hibernacula for Townsend’s big-eared bats.

In 2013, Jut led a team of researchers, undergraduate students, and citizen scientists on a multi-year study of Wupatki earth cracks. Their overarching goals are to: (1) expand upon earlier cave-dwelling arthropod work; (2) conduct annual counts of hibernating bats each winter; (3) identify other vertebrates using the earth cracks; (4) acquire long-term (at least one year) temperature and relative humidity data to establish cave climate trends; and, (5) collect cave sediment and bat muzzle swabs to test for the presence of white-nose syndrome.

Results

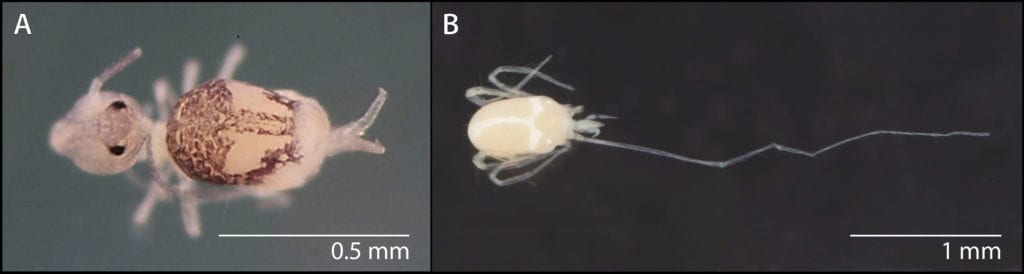

Only preliminary results are available for cave-dwelling arthropods. Presently, approximately 65 morphospecies have been identified. Two groups (Collembola and Acari) have been parsed tentatively into morphospecies, but will require further study. Of these, at least two new arthropod species (shown below) have been discovered. One species of springtail is an obligate troglophile Disparrhopalites naasaveqw, which has been formally described. The second species is a spectacularly troglomorphic Linopodes sp. This mite has antenniforms (modified front legs) more than three times the length of its body! To date, this is the only known troglobiont from Wupatki.

Bats continue to use Wupatki earth cracks for hibernation. Jut and others have monitored four of these roosts annually from 2013 through 2015 and from 2018 to 2019. The total number of Townsend’s big-eared bats for all caves combined ranged from 12 to 23 individuals per year. During each survey, at least one Myotis sp. was also recorded (one shown above). As species level identification for most Myotis bats requires examining the arrangement of teeth, species level identifications were not possible — handling bats during the winter would stress the animals and may result in them not surviving the hibernation period.

Most of the vertebrates encountered in the earth cracks were accidental occurrences. Plains spadefoot toads (Spea bombifrons) were observed on two different occasions, and a desert cottontail rabbit (Sylvilagus audubonii) skeleton was found at the bottom of one of the fissures. However, a woodrat (Neotoma spp.), as well as extensive woodrat midden material was observed in one fissure; this animal is probably a troglophile.

Conservation and Management

Fortunately, most of the Wupatki earth cracks receive little to no human visitation. With the exception of one fissure (which is jointly managed by the USDA Forest Service and NPS), there has been no evidence of recent human use during any of our site visits. All earth cracks managed solely by the NPS are closed to recreational use. Access requires a special use permit. Approval from Native American tribes, who claim cultural affiliation with the monument, is also required. As a result, these features and the sensitive biological resources they support are largely protected.

El Malpais

Located in west-central New Mexico, El Malpais National Monument encompasses approximately 588 square miles (1,522 km2). Formed by at least eight major volcanic eruptions ranging in age from 100,000 to 3,000 years old, this national monument is a dramatic landscape comprised of vast expanses of pahoehoe and ʻaʻā lava beds, cinder cones, ice caves, and hundreds of lava tube caves.

During October 2007 and October 2008, Jut and colleagues conducted the second multiple cave study and the first all macro-taxa biological inventory. They conducted two site visits per cave at 10 monument caves and one cave on adjacent Bureau of Land Management lands. Identical to the Parashant study, their objectives were to: (1) catalog all taxa using caves, including the identification of endemic and sensitive subterranean-adapted invertebrates; (2) apply an experimental systematic sampling framework for inventorying arthropods; (3) draw between cave comparisons to gain inference into patterns of invertebrate species distributions, biodiversity, biogeography, and endemism; and, (4) provide recommendations to protect the sensitive biological resources within these caves.

Results

From this work, at least seven new species of cave-dwelling arthropods (including two potential troglobionts) were identified. Importantly, two unique microhabitats were documented within these caves. Tree root “curtains” hanging from the ceilings occur within two caves, and moss gardens (a relict habitat) occur within cave entrances of three caves.

Within the moss garden habitat, a new species of millipede was discovered. This animal, Austrotyla awishoshola, is believed to be restricted to this habitat and is a presumed relict of the Ice Age. Incidentally, this millipede was named using the Zuni Native American terms awisho and shola. Awisho means “moss” and shola “many-legged creature.” Hence, ” many-legged creature of the moss”.

For bats, continued use of the largest known hibernaculum of Townsend’s big-eared bats (which included one big brown bat (Eptescus fuscus) torporing near the entrance) and two maternity roosts were confirmed. The maternity roosts consist of the largest known Mexican free-tailed bat colony in the region, and the largest known Townsend’s big-eared bat colony on the monument.

Conservation and Management

Protection of moss gardens: Moss garden habitats within cave entrances support an impressive community of bryophytes and are considered one of the most biologically unique features in the region. This habitat also supports at least two presumed relict species. Incidentally, caves with moss gardens boasts among the highest biological diversity of cave-dwelling arthropods. Thus, the caves and moss garden habitats should continue to receive the highest level of protection.

Courtesy Kyle Voyles.

Two of the caves with moss garden habitat are frequented by tourists. At one cave, the National Park Service roped off the habitat and have interpretative signs describing the importance of this habitat and its animal communities. The exclosure should be routinely inspected and maintained — as this is the only known locality for A. awishoshola. Also, it is of the utmost important to all rope off the moss garden habitat within the other cave and provide interpretative signs as well.

Protection of bat roosts: Fortunately, the monument has either permanently or seasonally closed all bat roost caves. The cave supporting the Mexican free-tailed bat roost has been permanently closed, while the Townsend’s big-eared bat maternity roost is closed during the spring and summer. Both closures have been in effect for nearly two decades. As a result of this work, the hibernaculum cave is now closed to recreational use during the winter months.

Scientists and managers know little about the winter habitat requirements of year-round bat residents at El Malpais. Thus, more surveys are needed, particularly winter bat inventories, to identify additional hibernacula. Annual to biennial monitoring of the known hibernaculum, as well as newly identified hibernacula is also needed. Additionally, long-term microclimatic monitoring in caves supporting hibernating bats should be conducted. In light of the westward advance of white-nose syndrome and global climate change, this information may be useful in guiding management decisions to protect bat populations in the future.

Further Reading

Courtesy Nicholas Glover.