Belize represents a very special place. In 2001, Jut was invited to conduct a biological inventory of Actun Chapat cave in the Cayo District (see below for results). This was his first glimpse of a cave ecosystem through the eyes of a budding scientist. In the ensuing several days studying this cave, he was hooked. The winding passageways. The colossal rooms festooned with a variety of stalactites and stalagmites. Traces of the ancient Maya adorned nearly every vista. The near uncomfortable silence perpetually and shatteringly interrupted by droplets of water gently cascading into otherwise still pools of water. The acrid smell of bat guano. The bats. The bugs. The jaguar. In a nutshell, the spectacular diversity of the neotropical subterranean world was transformative. It was on this expedition where Jut realized he would become a cave scientist.

In July 2019, Jut returned to Belize to conduct a multiple cave study at Runaway Creek Nature Reserve. This page summaries the findings of these two expeditions separated by nearly 20 years of time and experience.

Background

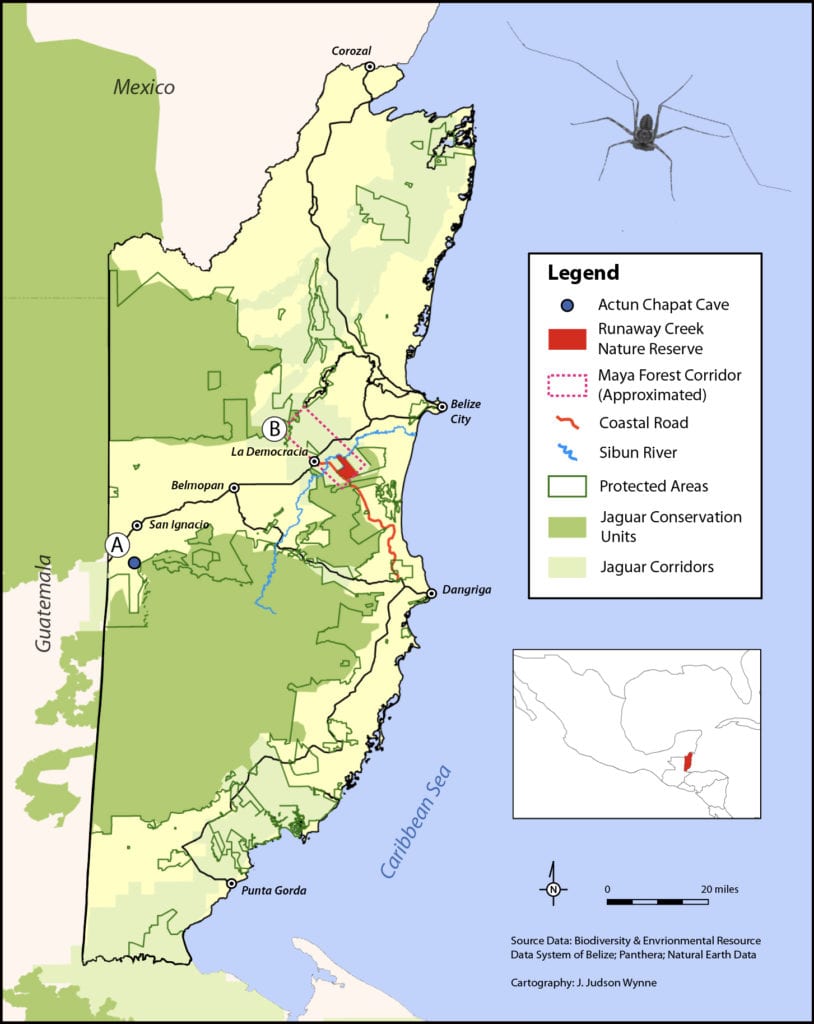

Belize is a small Central American country, which is part of the Yucatan Peninsula. It is bordered by Mexico to the north, Guatemala to the west and south, and the Caribbean Sea to the east. Belize’s land area covers 14,292 square miles (23,000 km2) with its near-coastal waters dotted by hundreds of islands and cays. The climate is subtropical. Vegetation within the Belizean interior is characterized as pine savannah in the lowlands and broad-leaf tropical forest on the karst hills and submontane regions.

Essentially, Belize is one big cave. With annual rainfall ranging from 60 inches (152.4 cm) in the north to 160 inches (406.4 cm) in the south and most of the country is comprised of one type of sedimentary rock (limestone), this represents the perfect ingredients for cave formation. As rain falls, it picks up atmospheric carbon dioxide forming a weak carbonic acid. This water-carbonic acid solution then percolates through the soil and rock, slowly dissolving the limestone and forming caves.

As a result, Belize boasts some of the world’s largest passageways, domed rooms, and exquisite cave formations. The ancient Maya used these majestic features extensively for numerous ceremonial purposes. They believed caves provided access to Xibalba (the Maya underworld). Because of this, Belize also contains the greatest concentration of significant archaeological caves within its borders.

Caves are typically the focus of archaeological investigations. Many of these studies are conducted to better understand the relationship between the ancient Maya and the subterranean realm. In other cases, scientists are literally racing against the looters, who remove the material culture and often wrought irreparably damage the ancient history and culture of the region.

Despite considerable scientific focus on caves, little is presently known regarding the subterranean biology of Belize. Bats are the most thoroughly studied of the cave dwellers. Scientists with the Wildlife Conservation Society spent nearly three decades studying Belizean bats. Of the 72 known species, 33 roost are known to roost in caves. Of these, 39% are pollinators and 55% are seed dispersers of native plant species. Incidentally, protecting both bat species and their cave roosts are critically important to maintaining the health of Belize’s native ecosystems.

Much less is known for the other inhabitants. Prior to the work at Runaway Creek, there have been only three community level arthropod studies. The first study was conducted in the Chiquibul Cave System (one of the largest in Central America), another study led by Jut in 2001 at Actun Chapat, and the third study represents the first multiple cave biological inventory of seven Toledo District caves. Through synthesizing the results of these efforts and other papers describing new arthropod species, at least 141 species of cave-dwelling arthropods are known to Belize. Of these, 28 are identified as subterranean-adapted (yet only 17 have been formally described).

Actun Chapat

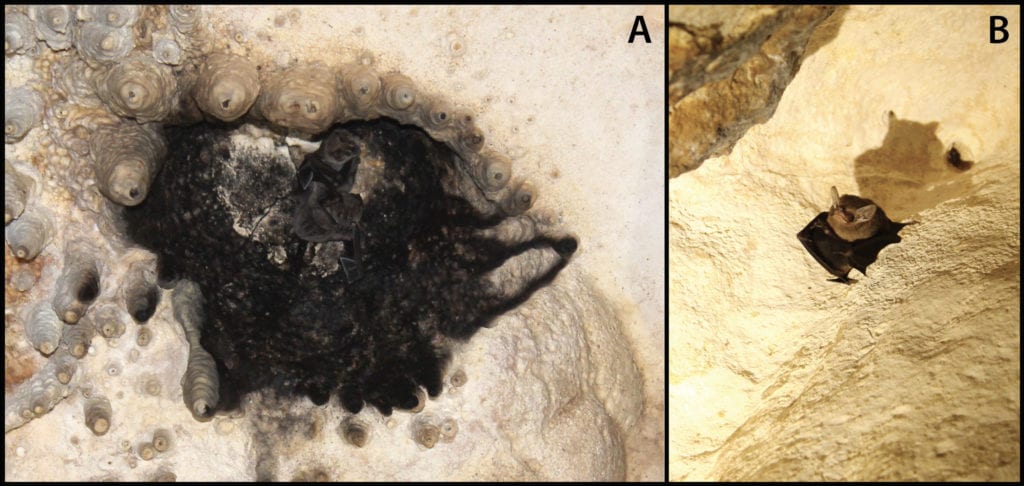

This project synthesized both field data and information in the literature on both invertebrate and vertebrate species observed in Actun Chapat in 2001. From this work, 25 cave-dwelling invertebrates were identified. Additionally, based upon research conducted by Dr. Bruce Miller of the Wildlife Conservation Society, Jut, and others, at least 10 bat species are known from this cave. Of conservation interest, an exceptionally large maternity roost of funnel-eared (Natalus stramineus) and ghost-faced (Mormoops megalophylla) bats occurs within one of its chambers – easily supporting over a hundred thousand of bats.

Courtesy Simon Jacyna.

Three creatures were identified lurking in the twilight. The Alfredo’s rainforest frog (Eleutherodactylus alfredi), Maya night lizard (Lepidophyma mayae), and the yellow-spotted night lizard (Lepidophyma flavimaculatum) were found at the bottom of the sinkhole entrance. These animals were attracted to the abundance of insect prey falling to the cave floor. A spectacular chimney effect within the sinkhole entrance resulted in the cave “inhaling” surface air during the day. Due to the strength of this “vacuum,” insects and even birds were sucked into the cave as they flew over it. A spiraling swarm of insects resulted as these animals attempted to fly out of the cave, against the strong wind current. Those unable to free themselves became exhausted and retired to the cave floor. There, a host of predators (frogs, lizards, and spiders) laid in wait for these weary insects.

acanthochela) known to both Actun Cebada and Actun Chapat caves. It occurs along the silty banks of subterranean pools. Courtesy Doug Billings.

Based on limited field research and a review of literature, Jut and colleagues identified two areas within the cave which should be protected. These ecologically sensitive areas were the large multiple species bat roost and a subterranean pool containing troglobionts (terrestrial subterranean-adapted) and stygobionts (aquatic subterranean-adapted; crab featured at left). To minimize disturbance associated with ecotourism, adventure-seekers should avoid these areas.

Ideally, an intensive systematic ecological survey of Actun Chapat with data collection over multiple seasons using a suite of survey techniques should be endeavored. This information will likely identify more endemic species and provide a more complete list of sensitive animal species. Only through such an effort will conservation biologists and resource managers have the data necessary to develop an evidence-based management plan for this cave.

Runaway Creek Nature Reserve

In central Belize, two concurrent government projects are rapidly proceeding with opposing ramifications. Paving the 37 mile Coastal Road will drastically change land use and accelerate natural resource exploitation along the road corridor, while the Maya Forest Corridor (MFC) aims to protect a vast swath of land providing genetic connectivity for charismatic rainforest animals, such as the jaguar and tapir. Within the MFC, the Runaway Creek Nature Reserve (RCNR) is considered the linchpin for success, yet the reserve also borders the to be paved Coastal Road.

In July 2019, Jut and Runaway Creek field biologists conducted a five cave all macro-taxa biological inventory. Although baseline line in nature, their overarching goal was to suffuse the significance of cave biological resources into the planning of the Maya Forest Corridor, while highlighting the likely impacts of the road paving project will have on sensitive cave resources. This objective were undergirded by their desire to contribute to the region’s natural history through characterizing cave use by bats and surface-dwelling animals, as well as identifying new and endemic species of cave-dwelling invertebrates.

For arthropods, cave deep zones were the focus in four of the five caves. The objectives were to identify new and endemic cave-restricted arthropod species, identify species of potential management concern, and provide the foundation for an inventory and monitoring program. Although their findings are preliminary, at least 64 morphospecies have been identified– including 16 troglobionts, 46 troglophiles, two parasites, and two accidentals. Of these, nearly 20 are likely to represent species new to science.

Regarding bats, four of our five caves were multi-species maternity roosts. Because the work was conducted during the middle of the summer (the maternity season), bats were not captured for identification. The team did not want to risk stressing the mother bats or potentially harming the pups.

Some of Belize’s most charismatic megafauna use Runaway Creek caves. We found Jaguar (Panthera onca) tracks in all five caves, Morelet’s crocodile (Crocodylus moreletii) tracks in three of five caves, and evidence of puma (Puma concolor) in at least two caves. The 2019 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species lists Jaguar as “Near Threatened” with a decreasing population trend, the Morelet’s crocodile as “Least Concern” with a stable population, and the puma is “Least Concern” with a decreasing population trend.

Future Research and Management

To best protect RCNR caves and the sensitive animals they support, the following future research activities should be undertaken. (i) Bat inventories should be conducted using mist nets and/ or harp traps so that bats can be captured and identified to species. (ii) All cave-dwelling animals should be sampled using systematic and repeatable techniques (which can facilitate future monitoring programs, if necessary). (iii) A long term trail camera monitoring (between three months to one year) program should be established to document how jaguar (and puma) are using caves and to confirm whether crocodiles are using these caves year-round. Additionally, once the information is collected and analyzed, a vulnerability assessment of current and predicted future human pressures should be conducted for the nature reserve. In the aggregate, these data can be used to develop a resource management plan for RCNR caves.

While the Maya Forest Corridor project may offer some conservation benefits, the paving of the Coastal Road will create new challenges for Runaway Creek. The following recommendations are provided in hopes of ameliorating some of these challenges.

Establishment of buffer around Runaway Creek: In particular, purchase of strip of land between Runaway Creek and the Coastal Road. There are efforts underway by the Foundation for Wildlife Conservation to purchase these lands (go here to contribute to this initiative).

A 24-hour on site presence: This may ultimately be required to reduce poaching and trespassing. Once the road is paved, poaching and other unauthorized activities are expected to accelerate.

This vehicle was illegally parked on the RCNR property. The poachers were probably hunting paca. Poaching at Runaway Creek will become more frequent once the Coastal Road is paved.

Creation of wildlife overpasses and underpasses: Both jaguar and tapir presently freely move across the Coastal Road. For these movements to continue relatively unimpeded, wildlife overpasses should be constructed in areas known to be used by these animals. Additionally, although the area is prone to flooding, wildlife underpasses (i.e., a network of culverts) is still worth considering for intermittent use by smaller animals. Currently, there are no plans to protect or sustain movement corridors of animals.

Educational outreach: Develop an education program to further heighten awareness regarding the importance and sensitivity of cave biological resources at Runaway Creek– it’s possible this program could be coordinated through the Belize Zoo.

Preliminary findings: Runaway Creek cave arthropods

Two of Jut’s former undergraduate students produced a video as their poster presentation of the Runaway Creek arthropod work at the 2020 NAU (virtual) Undergraduate Research Symposium, Flagstaff, Arizona. To view their poster, go here.

Further Reading