Background

Te pito o te huena (Rapanui for “naval of the world”), Rapa Nui (Easter Island) is the most remote inhabited place on earth. As with all oceanic islands, Rapa Nui is volcanic in origin. Three distinct volcanoes, roughly located in each corner of this triangular shaped island, gave rise to its existence in the middle of the South Pacific Ocean. Slightly more than 62 square miles (100 km2) in size, Rapa Nui is located approximately 2,237 miles (3,600 km) west of continental Chile and roughly 1,289 miles (2,075 km) east of the Pitcairn Island chain.

The island is famous for its towering statues (called moai) and the environmental catastrophe that occurred. As the Rapa Nui society flourished and the island’s nearly 1,000 iconic moai statues were being carved and moved across the island, an island-wide extinction event was under way. Due to a combination of the island’s extreme isolation restricting the ability for plants and animals to colonize, a fragile, fire-intolerant ecosystem, and an extended drought—a catastrophic ecological shift took place.

Rapa Nui is quite different from what the first Polynesians observed. Today, the once lush palm-dominated landscape has been transformed to a grassland punctuated by patches of invasive Eucalyptus trees. Most native plants no longer exist, and all native terrestrial vertebrates were driven to extinction by man’s hand. Today, nonnative invasive plants and animals dominate the landscape.

Of the over 400 known insect species known to the island, only about five percent are believed to be either endemic (evolved on the island and only known to occur there) or indigenous (arrived and became established without man’s assistance).

Since 2008, Jut has led five research trips to Rapa Nui. His work consisted of two major campaigns. Jut’s first four trips (2008-2011) revolved around his PhD research on cave ecosystems in the Roiho District, northeast of Hanga Roa village. In 2016, as a Fulbright Scholar, he led a campaign (for over three months) to conduct the largest islandwide effort to search for and document the remaining endemic insects on the island.

Cave Biology

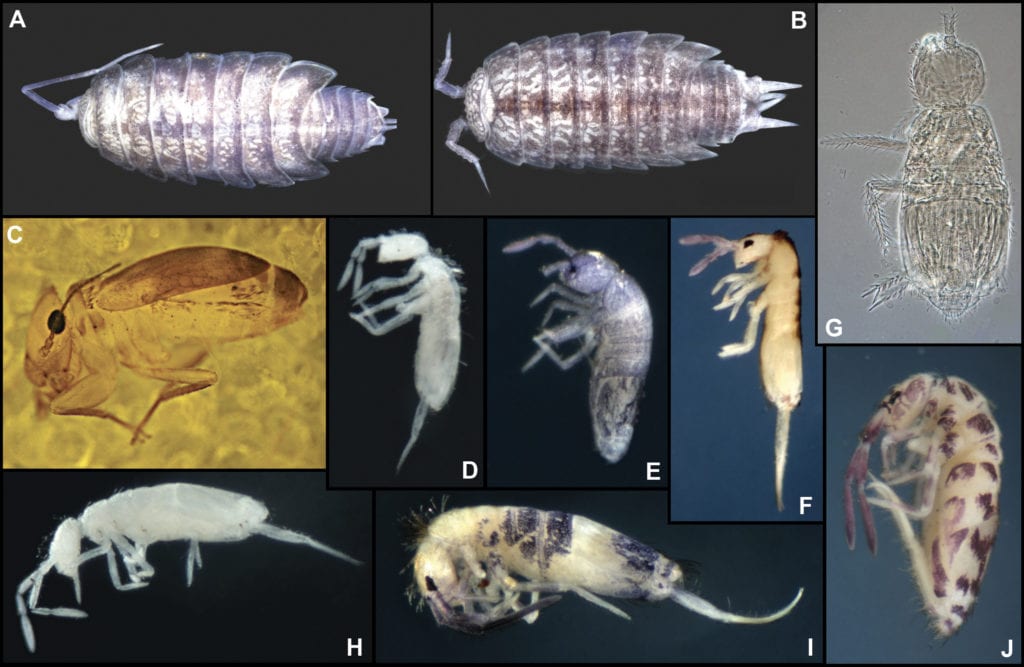

Our knowledge of Rapa Nui cave biology is rather limited. Most entomological research over the past 100 years focused on surface ecosystems. Prior to the work by Jut and collaborators, only one native arthropod species was documented within caves. This Collembola (or springtail) species, Coecobrya kennethi (Panel H below), was known from one cave. It was later identified as a species endemic to the island.

Over four research trips (from 2008 through 2011), Jut and several research teams studied the invertebrate communities of 11 caves on the Roiho lava flow. While most of the invertebrates inventoried represented nonnative alien species, they made some amazing discoveries. Firstly, they discovered eight previously unknown endemic species believed to be restricted to the cave environment. All of these new discoveries were named after either prominent Rapa Nui community members or with phrases of the Rapanui language.

This work also gave rise to the development of two hypotheses (refer to Wynne et al. 2014 for more information). On Rapa Nui, as all of the invertebrates’ (figure above) distributions appear limited to areas that experienced minimal historical human disturbance (i.e., cave entrances which retain native plant communities). So, the “disturbance relict hypothesis” was proposed to explain this phenomenon. These arthropods are relict species due to human disturbance and are postulated to be restricted to cave entrances and perhaps surface ecosystems with native vegetation.

As habitat loss due to human activities continues to accelerate globally, alas we anticipate more “disturbance relicts” will be identified in other ecological settings — most likely in areas where remnant pockets of native habitat occur amid large tracts of human disturbance.

For the two species known to Rapa Nui and other Polynesian islands (Styloniscus manuvaka and Lepidocyrtus olena), their discoveries prompted the “canoe bug hypothesis”. Ancient Polynesians once sailed vast expanses of the South Pacific in large twin-hulled voyaging canoes. During their passages, they transported various plant species used for food, medicine, and other utilitarian purposes in gourds. Within these gourds was soil and within the soil was invertebrates. Upon arrival to a new island, the Polynesians would often transplant these plants. As this occurred, they also transplanted these stowaway invertebrate species to new island habitats.

Jut hopes to test the canoe bug hypothesis by resampling these islands and then analyzing the specimens using comparative molecular techniques.

10 New Cave-restricted Insects from Rapa Nui

Island-wide Endemic Invertebrate Survey

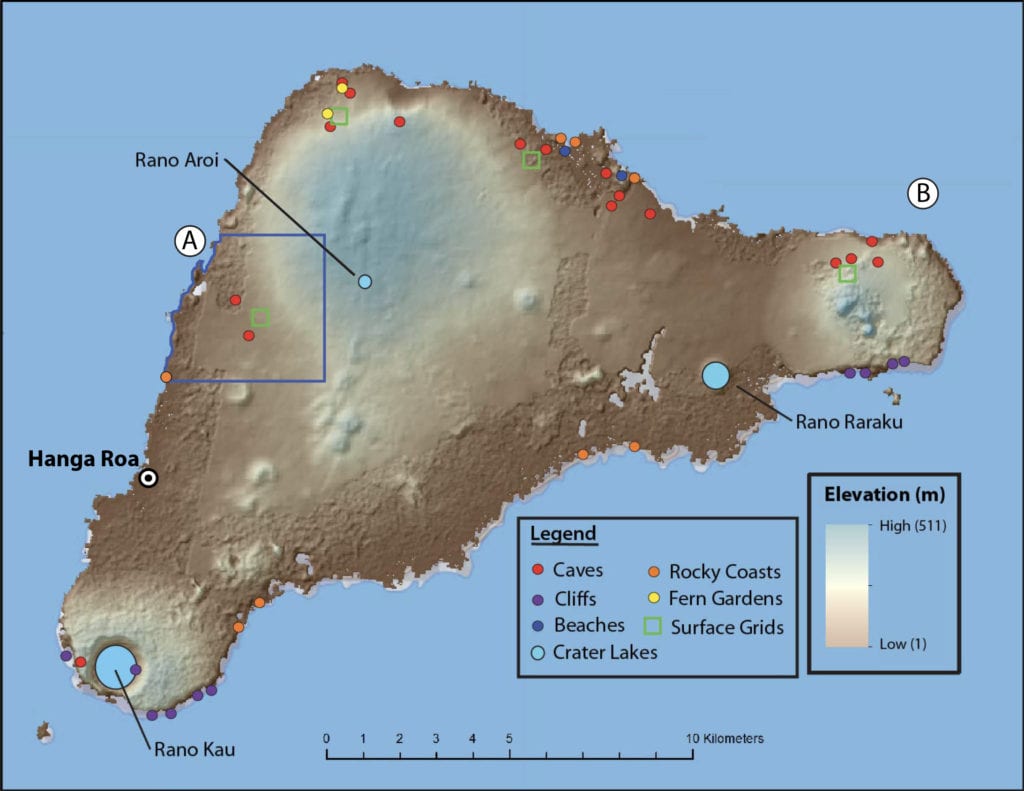

In 2016, Jut was awarded a Fulbright fellowship (for a video discussing his preliminary results go here). This award enabling him to continue his research on Rapa Nui. While there, he conducted the first island-wide expedition to search for endemic invertebrate species in some of the most difficult to access environments on the island — caves, cliffs, coasts, and crater lakes. These areas were posited to support native vegetation and thus represent the last vestiges of Rapa Nui’s ancient ecosystems.

During this work, he and a team of undergraduate students, citizen scientists, and members of the Rapa Nui community sampled 47 sites across the island including 20 caves, 10 cliff faces, the three crater lakes, eight rocky coastlines, the two main beaches, and two inland surface areas containing patches of native ferns.

From the materials examined thus far, at least 32 distinct morphological species groups have been identified including nine potentially undescribed (i.e., new and potentially endemic) species, three new island records of nonnative species, and the range expansions for at least three well-established invasive species. Jut and colleagues also provided recommendations for future research and monitoring, as well as a framework for managing the area supporting the 10 previously discovered endemic species. To read the report which discusses both preliminary findings, as well as management recommendations for Roiho District caves, go here.

Currently, Jut and Northern Arizona University undergraduate students are finalizing the identifications of the cliff specimens and have sorted and organized most of the cave specimens. For the cliff-dwelling arthropod specimens, those believed to represent new species will be sent to taxonomic specialists for further study and potentially formal description. He and his students will then develop a paper based upon their findings.

Investigación Insectos Endemicos de Rapa Nui

Further Reading

Wynne, J.J. 2017. The hunt for endemic insects on Easter Island. Scientific American.